Note: This article addresses diabetes mellitus, not diabetes insipidus. Although the two share the same reference term "diabetes" (which means increased urine production linked to a siphon (the kidneys), diabetes insipidus is much rarer and has a different underlying cause.

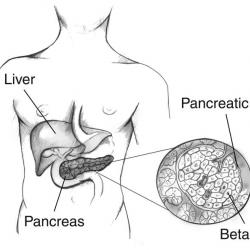

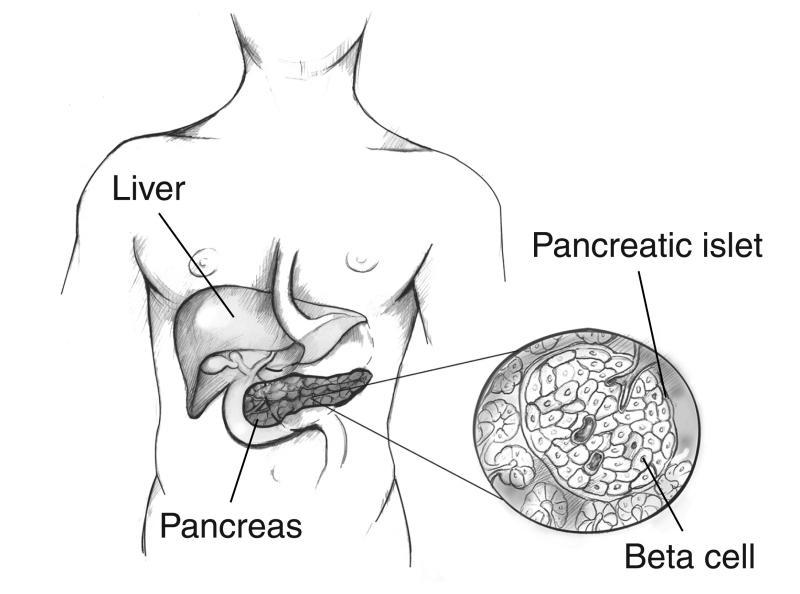

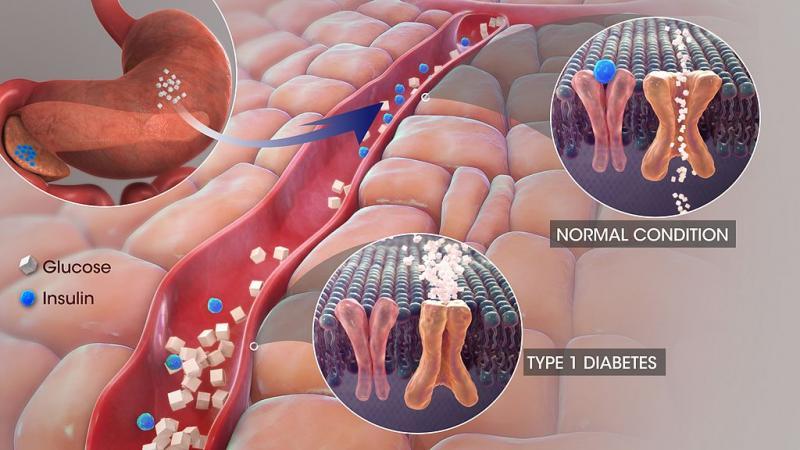

Diabetes mellitus is a condition in which the level of glucose (sugar) in an individual's blood becomes too high because the body cannot use it properly. About 4 million (6%) people in the United Kingdom have diabetes. It results either from an inability to produce insulin or because the individual's body has become resistant to the insulin produced. Insulin is a hormone, produced by the beta cells of the pancreas, which controls the movement of glucose into most of the body's cells via the blood circulation and maintains blood glucose levels within a narrow concentration range. Most tissues in the body rely on glucose for energy production, and all but a few - such as the brain and nervous system - are entirely reliant on insulin to deliver this essential fuel.

Diabetes disrupts the normal balance between insulin and glucose. Usually after a meal, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose and other simple sugars. This causes blood glucose levels to rise and stimulates the pancreas to release insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin allows glucose into the cells, where it also promotes storage of excess glucose - either as glycogen in the liver or as triglycerides in adipose (fat) cells.

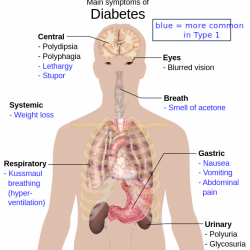

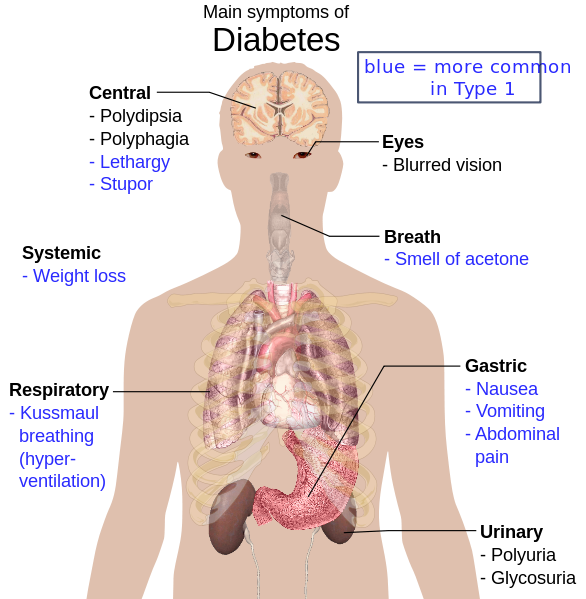

If there is insufficient or ineffective insulin, glucose levels remain high in the bloodstream and the body's cells "starve." Since glucose is not available to the cells with severe insulin deficiency, the body may attempt to provide an alternate energy source by breaking down fatty acids from fat cells. This less efficient process leads to a build-up of ketones (by-products that result from the use of fat as an alternative energy source when glucose is unavailable) and upsets the body’s acid-base balance, producing a state known as ketoacidosis. Ketones can be smelt on the breath (described as ‘pear drops’) but a large proportion of the population (including health care professionals) cannot smell ketones so this sign can be missed.

This can cause both short term and long term problems depending on the severity of the imbalance. In the short term it can upset the body's electrolyte balance such as causing low sodium and high potassium. The high blood glucose concentrations increase the amount of urine produced which leads to increased urine output (polyuria), including at night (nocturia), dehydration and then thirst. The large amount of fluid needed to be drunk due to thirst is called polydipsia. If unchecked, this can eventually lead to loss of consciousness, kidney failure and death. In the longer term, sustained high glucose levels can damage blood vessels, nerves, and organs throughout the body, contributing to other problems such as high blood pressure, heart disease, kidney failure and loss of vision in addition to diabetes.