There are a variety of laboratory tests that can be performed to diagnose and monitor breast cancer and its treatment. These tests can be broken down into four groups, based on the purpose of testing:

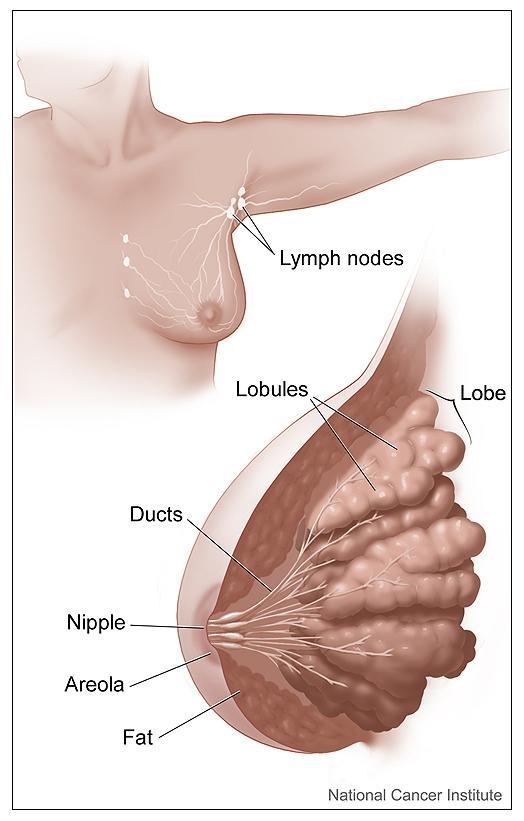

When a radiologist detects a suspicious area on a mammogram, more tests need to be done to see if it is a cancer. Abnormalities on mammogram may include finding micro calcifications (tiny white dots on mammogram), masses (where there appears to be a lump on the x-ray), or areas of distortion in the breast tissue. Whilst all of these may be associated with breast cancer they can also be caused by non cancerous (benign) breast disease and 75% of women recalled with abnormal mammograms will not have breast cancer. Also a palpable breast lump may be caused by a cyst or a fibro-adenoma which is not cancerous. Therefore any woman with a breast lump or abnormal mammogram will need more testing before a diagnosis can be made. This may be done by requesting more images of the breast with more in-depth scans (such as an ultrasound or MRI) or by a biopsy of the lump or suspicious area. For a biopsy, a small sample of tissue is taken under local anaesthetic from the suspicious area of the breast so that a pathologist can examine the tissue for signs of cancer – termed a core biopsy. This may be done under radiological guidance (so the doctor knows where to aim the needle) if the lump cannot be felt easily. Occasionally a fine needle aspiration is performed to extract cells to be examined by a pathologist. Rarely, if a definite diagnosis cannot be made after two or more attempts at core biopsy, then the lump may be removed surgically, termed an excision biopsy or a sample taken, termed an incisional biopsy.

The testing of biopsy material for cancer involves looking at cells under a microscope for evidence that cells have become malignant (changed from normal breast cells to cancer cells). Needle aspirations (where a fine needle is inserted into the lump and a few cells are removed) are limited in that they only show if malignant cells are present. A tissue biopsy is needed to determine if the cells are non-invasive or invasive as this involves removing a small sample of tissue and shows whether the cancerous cells have actually invaded into the surrounding tissue or not.

- If the pathologist's diagnosis is invasive carcinoma, there are several tests that may be performed on the cancer cells that guide in treatment and prognosis of the patient. The most useful of these are oestrogen and progesterone receptors and Her-2/neu.

- Oestrogen and progesterone receptor status are immunohistochemical tests and look for the presence of proteins that act as receptors for the female hormones oestrogen and progesterone. In tumours that have these receptors, normal female hormones bind to these receptors and cause the cancer cells to grow and divide more rapidly. The presence of these receptors are very important prognostic markers in breast cancer, and the higher the percentage of overall cells positive for the hormonal receptors the better the prognosis. If there are a significant number of oestrogen receptors, it is known as oestrogen-receptor positive breast cancer (ER+). If not, it’s known as oestrogen-receptor negative breast cancer (ER-). Progesterone receptors are not routinely tested for in many UK centres unless the breast cancer is oestrogen receptor negative. 70% of breast cancers are oestrogen receptor positive. If a tumour is both ER and PR receptor negative hormonal therapies will not help and these cancers carry a worse prognosis. Current hormonal therapies block the conversion of other hormones in the body to oestrogen (e.g. anastrozole, letrozole also known as aromatase inhibitors) or interferes with how oestrogen binds to these receptors (e.g. tamoxifen). The treatments differ for premenopausal and postmenopausal women, as in premenopausal women the ovaries are the main source of oestrogen production and treatment is usually directed at blocking this.

- Her-2/neu is receptor that is found on the surface of certain cancer cells. It is found in many different cancers and is not specific to breast cancer. It is made by a specific gene called the Her-2/neu gene which causes the cancer cells to make an excess of the Her-2 receptor. The faulty gene only occurs in cancer cells and is not a gene that you can inherit from your family. Some breast cancer cells have a lot more Her-2 receptors than others. In this case, the tumour is described as being Her-2-positive. It is thought that about 15% of women with breast cancer will have Her-2-positive tumours. Human epidermal growth factor, which occurs naturally in the body, can bind to these Her-2 receptors causing the cancer cells to grow and divide more rapidly. Because of this Her-2-positive breast cancers tend to be more aggressive than other types of breast cancer. However, fortunately there are treatments that specifically target the Her-2 receptor preventing growth of the cancer cells and it is therefore important to know if a tumour is Her-2 positive or not. This treatment called Herceptin (Trastuzumab) blocks these Her-2 protein receptors, preventing the human epidermal growth factor from attaching and preventing growth of the tumour cells. Herceptin can therefore be used after surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer returning or can often be used to shrink the cancer before surgery. It can also be used to treat the cancer after it has returned or spread. There are two common techniques used to determine Her-2/neu status in breast cancer and to see whether or not a tumour is Her-2 positive: immunohistochemistry (a method for detecting the amount of the Her-2 protein in the cells) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which determines the amount of the Her-2/neu gene in each cell. Currently, the gold standard for assessing Her-2/neu status is immunohistochemistry, and the results are scored as 0, 1+, 2+ and 3+ where 0 and 1+ are considered negative results. A 3+ result is considered positive and means that there are significant levels of the Her-2/neu receptor in the cell and the cancer is therefore Her-2 positive. A 2+ result is less straightforward and means that a moderate amount of Her-2 protein has been found. As this is inconclusive, this result is usually confirmed by FISH testing to check as to whether the Her-2/neu gene is also present in significant levels in the cell. If the FISH result confirms that there are excessive levels of the Her-2/neu gene, the cancer would be described as Her-2 positive. Therefore, currently, FISH is used to confirm Her-2/neu positive status and eligibility for Herceptin in cases of 2+ immunohistochemistry.

Other laboratory tests may be used to help determine whether or not the tumour is responding to therapy or if it has recurred. The CA15-3 tumour marker, if elevated prior to treatment, is one such laboratory test, and is used after treatment, to monitor a patient for a recurrence of breast cancer. CA 15-3 is normally produced by the breast tissue and therefore some cancer-free individuals normally have a level of this substance in their blood and/or urine. This is especially true for pregnant or breastfeeding women where the breast tissue is more active. However, because in breast cancer the cells grow and divide more rapidly, the levels of Ca15-3 may increase as the cancer gets bigger, and give a higher result than expected. However not all breast cancers cause an increase in CA15-3 and it is unlikely to be significantly raised in early stages of breast cancer as not enough of the breast tissue is involved. Therefore, only a medical professional can evaluate whether the results of such a test are cause for concern. In general, because of these reasons, CA 15-3 is a poor screening test but an excellent surveillance test in some patients. This means that it is unreliable for detecting cancer (as it can be elevated in patients without cancer) but can be used to follow it once it has been diagnosed. It can therefore be used in select patients to see if the cancer has spread or recurred (where the levels of CA 15-3 in the bloodstream would be expected to increase) or to assess a response to a particular treatment.

There are additional tests that may be used in breast cancer cases, such as DNA ploidy, Ki-67 or other proliferation markers. However, these are not currently in routine use in the UK and most authorities believe that only Her-2/neu, oestrogen and progesterone receptors are beneficial. This is mainly because there is currently no treatment available that works for patients with positive results in these additional tests and also because studies have shown that they offer little information on prognosis. Some research centres use these tests for additional information in evaluating patients however most centres currently do not use them at all.

Finally, women who are at high risk for breast cancer because of family history can find out if they have the BRCA-1, BRCA-2 or TP53 gene mutation by taking a blood test. Since the BRCA genes normally help to protect a woman from developing breast cancer, a mutation in either gene indicates that the patient is at higher risk for developing the disease. Women who carry mutations in either the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 gene face a 60-80% lifetime risk of breast cancer. It is important to remember, however, that not all individuals with the mutation develop breast cancer and that most cases of breast cancer occur in women who lack mutations in either BRCA gene. A genetic counsellor should explain the meaning of the results and offer advice about options for decreasing risk. Counselling advice should be offered both before testing takes place and after receiving test results.